News

Cedit Newswise —

‘They were my age.’Milwaukee journalism students research lives, unearth photos of Vietnam dead

A team of University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee journalism students took on an unusual research project this spring – helping find the missing photos and stories of Wisconsin soldiers killed in Vietnam. With help from other volunteers, they succeeded in finding the final 64 missing photos of Wisconsin soldiers by Memorial Day Weekend.

Their efforts were part of the Faces Never Forgotten project, a national effort to find approximately 17,300 missing photos for a digital Wall of Faces planned for the new Vietnam veterans Education Center at The Wall in Washington, D.C. Organizers hope that photos will be found to accompany all 58,300 names listed on the Vietnam Memorial Wall.

(The photos found so far are online at http://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces) The Wisconsin project was completed just befoCrre Memorial Day when relatives confirmed that an old Milwaukee North Division High School yearbook photo showed Willie Bedford, the final image missing of the 1,161 Wisconsin service members who died in Vietnam.(Read student Rachel Maidl’s account of her search for the last image here: http://go.uwm.edu/1Ew04Il)With that confirmation, Wisconsin became the sixth state, and largest so far, to collect photos of all its service members killed in Vietnam. “The Wisconsin effort has been by far the most efficient and the most successful,” said George DeCastro, coordinator of the Faces Never Forgotten Program. “The high level of coordination and cooperation between all parties involved was astounding. And, of course, your students and all of the other volunteers are the ones who actually got it done.”Andrew Johnson, publisher of the Dodge County Pionier in Mayville, Wisconsin, spearheaded Faces Never Forgotten in Wisconsin. Jessica McBride, senior journalism lecturer at UWM, got her JAMS 320: Integrated Reporting classes involved after meeting Johnson in February 2015.

‘Stories that matter’“I thought it was an excellent way to teach basic research and storytelling skills, as well as the role the media can play in communities,” said McBride. “I want students to work on stories that matter. It’s moving how they embraced this cause.”

UWM, which enrolls more veterans than any other university in the state, was also a natural fit for the project. When the journalism class got involved in February 2015, 64 Wisconsin soldiers’ photos were missing. Even after the semester ended in mid-May, McBride and several students continued their search for the remaining photos with the help of other volunteer researchers.

North Dakota, South Dakota, New Mexico and Wyoming also have located all the missing photos, and Iowa is down to one missing, according to DeCastro.

Johnson had two very personal reasons for getting involved. The Education Center at The Wall also will project photos of the nearly 8,000 service members killed in action since Sept. 11. One of those soldiers is Johnson’s son, U.S. Army 1st Lt. David Johnson, who was killed in Afghanistan in January 2012. Andrew Johnson says Vietnam veterans, like those in the Patriot Guard, have been supportive of his family as they mourned David’s death. Patriot Guard members helped lead his son’s funeral procession and accompanied Lt. Johnson’s casket up until his burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

“Photos are so important in making a person ‘real,’” Johnson explains, adding that there are few photos of many of the soldiers who fought in the unpopular Vietnam War. Further compounding the problem is the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records center that destroyed approximately 16-18 million official military personnel files. When Johnson first got involved in the project, 400 photos from Wisconsin were missing.

Journalism students at UWM pored over cemetery records, checked phone directories and yearbooks, looked through veteran memorial sites and tracked down surviving family and friends any way they could – email, telephone, the U.S. Postal Service and in-person. Along the way, they got help from other volunteers: a veteran, a retired newspaper editor, a writer, a historical researcher, teachers and school officials who searched records and yearbooks, and a leader of the Wisconsin Association of Black Genealogists, who was also a UWM student.

Mourning sons, remembering friendsThe research trail was often long and difficult. Senior Justin Skubal’s soldier, Thomas Shaw, had left a widow, but she and Shaw’s mother had both remarried and tracking stepsiblings was challenging. Fellow senior Jonathan Powell agreed: “It’s difficult to dig up information when people remarry, and sometimes families seem to fall apart after a death.”

The project gave the students new insights into the sacrifices these and other soldiers had made. Skubal said he understands better why his stepfather, a Vietnam veteran, awoke some mornings startled and shaking

Students heard stories from families about the devastating impact of their losses; fellow soldiers told them details of the battles and seeing their buddies die.“This was way more than a class assignment,” says Powell. Echoing Johnson, he adds, “A soldier never dies unless he’s forgotten.”

“When we started this project, I thought about these Vietnam soldiers as old men, but they were my age, or my brother’s age,” says UWM junior Amanda Porter, who tracked down Sgt. Nathaniel Merriweather’s story and photo through cemetery records, help from the mayor of the small Tennessee town where Merriweather is buried, and an army buddy who remembered him. Touching an obituary photo of Merriweather on her computer screen, she said: “It gave me a warm feeling, but really sad. I’m grateful that they are going to be remembered and I was part of that.”

McBride, Johnson and the students were impressed by all those who have helped.

“This is a community effort. That’s what stands out to me,” McBride wrote in a May 20 story for “OnMilwaukee.com.”

“Younger generations and old have come together to find these. Students and veterans. Black, Latino, American Indian and white. Republican and Democrat. This is a community effort. And, to me, that means this exemplifies Wisconsin at its finest.”

Back in 2005, Kristofer Goldsmith thought he was prepared for war. Then just 19-years-old, the Army sergeant deployed to Iraq with the Third Infantry Division. It was a moment that he had been waiting years for.

“I wanted nothing more but to be in the military my entire life, from the time that I was a little kid,” he says.

Goldsmith’s assignment was to act as a documentarian and intelligence collector for his platoon. He wound up photographing mass graves, and dead Iraqi police officers and children.

“It was something that I wasn’t prepared to deal with,” he says. “Even when I got home, PTSD was little more than an acronym to me—I didn’t understand what it meant. I didn’t understand the way that it would haunt me for years, and possibly the rest of my life.”

In 2014, more than 530,000 service members received treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at facilities run by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Before he even left the military, Goldsmith says that PTSD began to affect his life. He was written up in 2007 for missing his flight to Baghdad for his second deployment. The reason why Goldsmith wasn't on that plane? He was in a hospital after attempting suicide the night before.

Goldsmith was hit with a misconduct charge for missing that flight, and he was subsequently forced out of the military with a general discharge—one rung below the honorable discharge that entitles veterans to full benefits. Because of his discharge status, he’s been denied access to healthcare services from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

“The Army knew why I missed my flight—when I survived my suicide attempt it was at Fort Stewart, Georgia, and I was found by military police,” he says. “I struggled for a year and a half, getting almost no help at all from the Army when I was asking for it, desperately.”

But Goldsmith’s case is not unique. Though 85 percent of the more than 2.5 million veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars have been released from their service with honorable discharges, 300,000 have been forced out of the military with less-than-honorable discharges. The U.S. government has acknowledged that some of these discharges were the result of PTSD.

Goldsmith says that the military could have prevented his suicide attempt but failed to act when his cries grew louder.

“Even when I told an Army psychiatrist that I was thinking about suicide, she told me that I had three choices,” he says. “She told me that I could one, suck it up, be a man, and I could deploy; two, I could go AWOL and live like a convicted felon for the rest of my life; or three, I could give up and commit suicide. Those were the suggestions that an Army psychiatrist offered me when I told her how I was feeling after struggling for so long with nightmares from Iraq.”

When Goldsmith approached the U.S. military and asked that his discharge status be changed because of his untreated PTSD, the Army reject his appeal. He has spent the last eight years trying to get Washington to recognize that PTSD is often the source of the behavior that gets many vets pushed out.

Congress has tried to put a stop to this practice—Section 512 of the 2009-2010 National Defense Authorization Act says that the Defense Department may not issue a discharge other than honorable if the service member has been diagnosed with PTSD or a traumatic brain injury. But since 2009, over 20,000 soldiers with mental health problems have been dismissed for misconduct. Without an honorable discharge, veterans cannot receive VA healthcare benefits.

"I think it's damn near criminal that you could take a person, send them to war, they come home sick, and then you don't even provide them healthcare once they get home," Goldsmith says.

In 2014, former Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel took things a step further and attempted to amend the rules regarding PTSD and discharge status. But Goldsmith says Hagel’s memo primarily focused on Vietnam-era veterans.

“Secretary Hagel’s memorandum was too narrow—it doesn’t effect my generation at all,” he says. “Today, the discharge review boards, they’re still not recognizing PTSD the way Secretary Hagel intended.”

Goldsmith says lawmakers in the House and Senate are signing on to the Fairness For Veterans Act, which he says will be formally introduced at the end of this week. He hopes to get others to sign on on to the bill, and is trying raise awareness among the public.

“We could use all the help in the world,” he says.

Click Here to see full story

Credit The Take Away

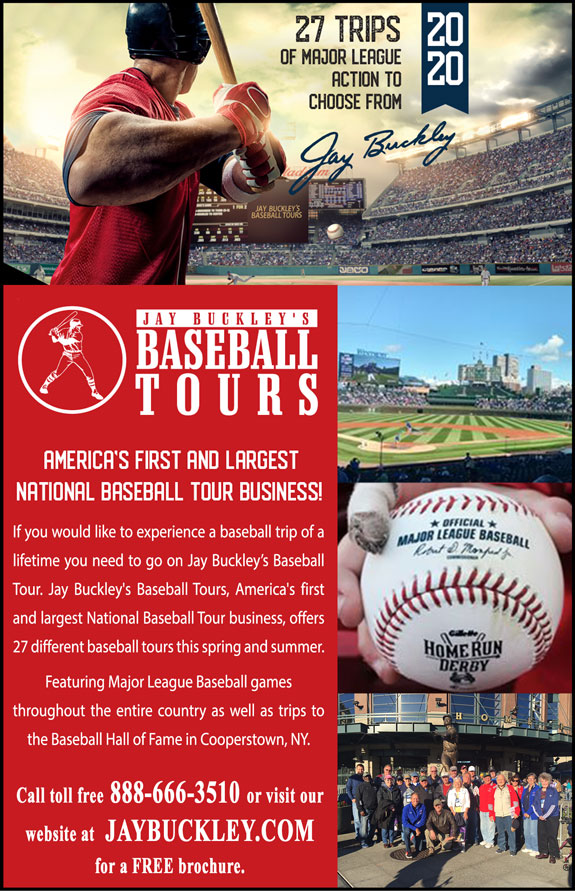

WASHINGTON — The National World War II Museum in New Orleans this week opens the Road to Tokyo, the first big exhibit on the Pacific theater campaign from the highly regarded museum that opened in 2000 with a focus on D-Day and the Normandy Invasion.

As the nation commemorates Pearl Harbor Day this week, here are the top 6 things that the museum’s chief historian would like Americans to know about the brutal – and initially unsuccessful – war that the US military was forced to wage against Japanese forces in the wake of what was, at the time, the most devastating attack ever on US soil.

The American public did not support President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s key early decision in the war.

The American public was so shocked by what they had seen at Pearl Harbor that they wanted to fight the Japanese first. President Roosevelt was arguing, however, that the Nazis were the greater threat.

“That’s not what the public wanted to hear. The public wanted revenge on Japan,” says Keith Huxen, senior director of history and research at the museum. “Historically, politically [FDR] was absolutely correct, but from that very first decision there were implications, and one of them was that we didn’t put the resources into the Pacific war that were being pumped into the European theater.”

As a result, he adds, “It meant that we were basically fighting the Pacific war on a shoestring budget, and [the American troops fighting it] didn’t get all of the help that they were entitled to.”

he destruction of the fleet at Pearl Harbor inadvertently ushered in a new era of US naval warfare.

After Pearl Harbor, the US Pacific fleet of battleships were hit hard. The primary remaining US resources were primarily in the form of aircraft carriers, submarines, and projection of air power.

“This is a really new way of fighting that we’re going to have to pioneer and master,” Dr. Huxen says. The new museum exhibit offers a mockup of the USS Enterprise, which ended up being the most successful American aircraft carrier during World War II. “We’re going to try out this new military doctrine, relying on these assets because we don’t have a choice – but at the time the jury was still out.”

Previously, naval warfare meant battleships (like those that the US lost at Pearl Harbor) pulling up alongside each other and blasting away. In the Pacific, “we’re playing a game of cat and mouse, launching torpedo and dive bombers to locate each others’ fleet and kill that way,” Huxen says. “It’s the first time in history where the opposing fleets never lay eyes on each other.”

The Pacific theater was a very different war than the one Americans waged in Europe.

There is first the matter of vast distances: It is four times the distance from San Francisco to Tokyo than it is, for example, from New York to London.

Once US troops arrived on the scene, there was far less infrastructure, including, say, docks and port facilities, or cities with roads.

“You sail thousands of miles to these places like Guadalcanal, and the hardest part of the journey is the last 100 yards,” says Huxen. “You have to get from the boat to the beaches, and when you do we basically have to build all these things: Make hospitals, clean water, food. And we have to do it again and again and again.”

Victory was not looking good in the early days of the war.

“When the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor, they didn’t want to invade California. Their idea was that we would negotiate a peace if they hit us hard enough. Pearl Harbor did allow the Japanese to knock us back on our feet for six or seven months, and during that time they were virtually unstoppable,” Huxen says.

May 1942 sees the fall of the Pacific corridor to the Japanese – what amounts to the height of the Japanese empire. In the six or seven months since Pearl Harbor, the Japanese had swept through all of Southeast Asia and across the southwestern Pacific. The Japanese had taken the Philippines as well.

“It was very frightening. We don’t have any victories at this point. If you can imagine an event like Pearl Harbor, and then there’s no good news for months on end.”

Against this backdrop comes the Battle of the Coral Sea, which is largely a draw between US and Japanese forces. “Both sides have success, but neither wins total victory,” Huxen says.

Still, though the performance wasn’t a win, it was a relief for the Pentagon. “It is the first time we kind of blunt the Japanese advance,” he adds. “Our military is OK – they’d have like to have seen better, but it wasn’t a disaster.”

The Battle of Midway was the US turning point in the Pacific.

The World War II Museum singles the battle out for special treatment in its new exhibition. For the Japanese, the island was critical. They wanted to take Midway, where the US had a base, then threaten Hawaii and end the war.

“On the first morning of the battle, what we want people to understand is that we were losing very badly,” Huxen says. The US military had sent three waves of planes out trying to locate the Japanese, but when they did they were being shot down.

Then suddenly, in a remarkable moment, two waves of US bomber planes converged on the Japanese fleet, and arrived at the moment when the Japanese fighter planes were at a lower altitude and hit three of the four Japanese carriers.

CLICK TO READ FULL STORY FROM CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR:

At 7:55 a.m. on Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese dive bombers, fighter bombers and torpedo planes attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor near Honolulu. Approximately 360 Japanese planes took part in the attack, which lasted less than two hours. The USS Oklahoma received nine torpedo hits in under twelve minutes that morning. It rolled over and sank in shallow water with more than 400 men still on board. Over the past six months, with a fresh mandate from the Defense Department, the unidentified bones of those onboard were exhumed from a cemetery in Hawaii and brought to a laboratory at Offutt Air Base in Nebraska, where scientists have begun the task of identifying the remains.

Read the full story by clicking here

WASHINGTON (Tribune News Service) — The babies and toddlers of soldiers returning from deployment face the heightened risk of abuse in the six months after the parent's return home, a risk that increases among soldiers who deploy more frequently, according to a study scheduled for release Friday.

The study will be published in the American Journal of Public Health. The abuse of soldiers' children exposes another, hidden cost from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan that killed more than 5,300 U.S. troops and wounded more than 50,000.

Research by the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia looked at families of more than 112,000 soldiers whose children were 2 years old or younger for the period of 2001 to 2007, the peak of the Iraq War. Researchers examined Pentagon-substantiated instances of abuse by a soldier or another caregiver and from the diagnoses of medical personnel within the military's health care system.

"This study is the first to reveal an increased risk when soldiers with young children return home from deployment," David Rubin, co-director of the hospital's PolicyLab and the report's senior author, said in a statement. "This really demonstrates that elevated stress when a soldier returns home can have real and potentially devastating consequences for some military families."

Rubin said the study will help the Army and other services learn "when the signal [of stress] is the highest and the timing for intervention to help the returning soldiers."

The Army said it will use the information to help serve soldiers and their families better.

"While incidents of child abuse and neglect among military families are well below that of the general population, this study is another indicator of the stress deployments place on soldiers, family members and caregivers," said Karl Schneider, principal deputy assistant secretary of the Army for manpower and reserve affairs. "Since the end of the data collection period in 2007, the Army has enacted myriad programs to meet these kinds of challenges head on, and we will continue working to ensure services and support are available to soldiers, families and their children."

The study focused on the first two years of a child's life because of the elevated risk for life-threatening child abuse among infants exceeds risk in all other age groups. In all, there were 4,367 victims from the families of 3,635 soldiers.

The rate of substantiated abuse and neglect doubled during the second deployment compared with the first, the study found. For soldiers deployed twice, the highest rate of abuse and neglect occurred during the second deployment and was usually a caregiver other than the soldier.

"The finding that in most cases, the perpetrators were not the soldiers thmselves reveals to us that the stress that plays out in military families during or after deployment impacts the entire family and is not simply a consequence of the soldier's experience and stress following deployment," said Christine Taylor, the study's lead author, a project manager the PolicyLab.

Researchers had an ongoing interest in the topic, Rubin said, which coincided with the Army's interest in determining how to better serve its returning soldiers and families.

A key finding was that mandatory reporting of child abuse by the Army to the Pentagon's Family Advocacy Program appears to have been largely ignored; 80 percent of the instances were not reported to the program. The program offers parenting instruction, child care and classes to ease a soldier's transition home. Those services may not be offered widely enough to meet the need, the study found.

World War I – known at the time as “The Great War” - officially ended when the Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919, in the Palace of Versailles outside the town of Versailles, France. However, fighting ceased seven months earlier when an armistice, or temporary cessation of hostilities, between the Allied nations and Germany went into effect on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. For that reason, November 11, 1918, is generally regarded as the end of “the war to end all wars.”

Soldiers of the 353rd Infantry near a church at Stenay, Meuse in France, wait for the end of hostilities. This photo was taken at 10:58 a.m., on November 11, 1918, two minutes before the armistice ending World War I went into effect

In November 1919, President Wilson proclaimed November 11 as the first commemoration of Armistice Day with the following words: "To us in America, the reflections of Armistice Day will be filled with solemn pride in the heroism of those who died in the country’s service and with gratitude for the victory, both because of the thing from which it has freed us and because of the opportunity it has given America to show her sympathy with peace and justice in the councils of the nations…"

The original concept for the celebration was for a day observed with parades and public meetings and a brief suspension of business beginning at 11:00 a.m.

The United States Congress officially recognized the end of World War I when it passed a concurrent resolution on June 4, 1926, with these words:

Whereas the 11th of November 1918, marked the cessation of the most destructive, sanguinary, and far reaching war in human annals and the resumption by the people of the United States of peaceful relations with other nations, which we hope may never again be severed, and

Whereas it is fitting that the recurring anniversary of this date should be commemorated with thanksgiving and prayer and exercises designed to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding between nations; and

Whereas the legislatures of twenty-seven of our States have already declared November 11 to be a legal holiday: Therefore be it Resolved by the Senate (the House of Representatives concurring), that the President of the United States is requested to issue a proclamation calling upon the officials to display the flag of the United States on all Government buildings on November 11 and inviting the people of the United States to observe the day in schools and churches, or other suitable places, with appropriate ceremonies of friendly relations with all other peoples.

An Act (52 Stat. 351; 5 U. S. Code, Sec. 87a) approved May 13, 1938, made the 11th of November in each year a legal holiday—a day to be dedicated to the cause of world peace and to be thereafter celebrated and known as "Armistice Day." Armistice Day was primarily a day set aside to honor veterans of World War I, but in 1954, after World War II had required the greatest mobilization of soldiers, sailors, Marines and airmen in the Nation’s history; after American forces had fought aggression in Korea, the 83rd Congress, at the urging of the veterans service organizations, amended the Act of 1938 by striking out the word "Armistice" and inserting in its place the word "Veterans." With the approval of this legislation (Public Law 380) on June 1, 1954, November 11th became a day to honor American veterans of all wars.

Later that same year, on October 8th, President Dwight D. Eisenhower issued the first "Veterans Day Proclamation" which stated: "In order to insure proper and widespread observance of this anniversary, all veterans, all veterans' organizations, and the entire citizenry will wish to join hands in the common purpose. Toward this end, I am designating the Administrator of Veterans' Affairs as Chairman of a Veterans Day National Committee, which shall include such other persons as the Chairman may select, and which will coordinate at the national level necessary planning for the observance. I am also requesting the heads of all departments and agencies of the Executive branch of the Government to assist the National Committee in every way possible."

President Eisenhower signing HR7786, changing Armistice Day to Veterans Day. From left: Alvin J. King, Wayne Richards, Arthur J. Connell, John T. Nation, Edward Rees, Richard L. Trombla, Howard W. Watts

On that same day, President Eisenhower sent a letter to the Honorable Harvey V. Higley, Administrator of Veterans' Affairs (VA), designating him as Chairman of the Veterans Day National Committee.

In 1958, the White House advised VA's General Counsel that the 1954 designation of the VA Administrator as Chairman of the Veterans Day National Committee applied to all subsequent VA Administrators. Since March 1989 when VA was elevated to a cabinet level department, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs has served as the committee's chairman.

The Uniform Holiday Bill (Public Law 90-363 (82 Stat. 250)) was signed on June 28, 1968, and was intended to ensure three-day weekends for Federal employees by celebrating four national holidays on Mondays: Washington's Birthday, Memorial Day, Veterans Day, and Columbus Day. It was thought that these extended weekends would encourage travel, recreational and cultural activities and stimulate greater industrial and commercial production. Many states did not agree with this decision and continued to celebrate the holidays on their original dates.

The first Veterans Day under the new law was observed with much confusion on October 25, 1971. It was quite apparent that the commemoration of this day was a matter of historic and patriotic significance to a great number of our citizens, and so on September 20th, 1975, President Gerald R. Ford signed Public Law 94-97 (89 Stat. 479), which returned the annual observance of Veterans Day to its original date of November 11, beginning in 1978. This action supported the desires of the overwhelming majority of state legislatures, all major veterans service organizations and the American people.

Veterans Day continues to be observed on November 11, regardless of what day of the week on which it falls. The restoration of the observance of Veterans Day to November 11 not only preserves the historical significance of the date, but helps focus attention on the important purpose of Veterans Day: A celebration to honor America's veterans for their patriotism, love of country, and willingness to serve and sacrifice for the common good.